But it will decrease rapidly beyond this point.

The current has decreased only slightly at this point. This breakdown torque is due to the larger than normal 20% slip.

#SYNCHRONOUS SPEED NS FULL#

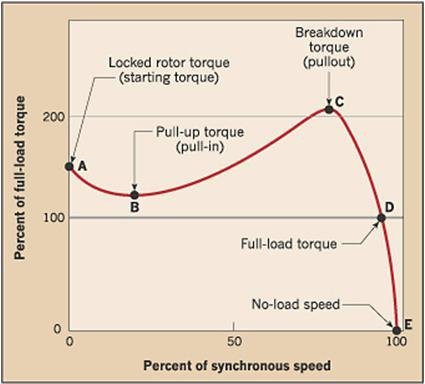

As the rotor gains 80% of synchronous speed, torque increases from 175% up to 300% of the Full Load Torque. This is the lowest value of torque ever encountered by the starting motor. The current is high because this is analogous to a shorted secondary on a transformer.Īs the rotor starts to rotate, the torque may decrease a bit for certain classes of motors to a value known as the Pull-Up Torque. Starting current known as Locked Rotor Current (LRC) is 500% of Full Load Current (FLC) - the safe running current. The Locked Rotor Torque is about 175% of FLT for the example motor graphed above. The above graph on Picture 2 shows that starting torque known as Locked Rotor Torque (LRT) is higher than 100% of the Full Load Torque (FLT) - the safe continuous torque rating. If the rotor spins a little faster, at the synchronous speed, no flux will cut the rotor at all (fr = 0 ). The 2.5 Hz is the difference between the synchronous speed and the actual rotor speed. The rotating magnetic field is only cutting the rotor at 2.5 Hz. Why is it so low? The stator magnetic field rotates at 50 Hz. Thus for f = 50 Hz line frequency, the frequency of the induced current in the rotor fr = 0.05 Slip at 100% torque is typically 5% or less in induction motors. Where s is slip and f is stator power line frequency. The frequency of the current induced into the rotor conductors is only as high as the line frequency at motor start, decreasing as the rotor approaches synchronous speed. Where Ns is synchronous speed and N is rotor speed. The ratio of actual flux cutting the rotor to synchronous speed is defined as slip: As the rotor speeds up, the rate at which stator flux cuts the rotor is the difference between synchronous speed Ns and actual rotor speed N (or Ns - N). The current induced in the rotor shorted turns is maximum as is the frequency of the current (the line frequency). The stator field is cutting the rotor at the synchronous speed Ns. When power is first applied to the motor, the rotor is at rest while the stator magnetic field rotates at the synchronous speed Ns. If the rotor were to run at synchronous speed, there would be no stator flux cutting the rotor, no current induced in the rotor, no torque. Thus, a loaded motor will slip in proportion to the mechanical load. It is the magnetic flux cutting the rotor conductors as it slips which develops torque. However, the slip between the rotor and the synchronous speed stator field develops torque.

If there were no mechanical motor torque load, no bearing, windage, or other losses, the rotor would rotate at the synchronous speed. The result is rotation of the squirrel cage rotor. The rotor field attempts to align with the rotating stator field. The rotating stator magnetic field interacts with this rotor field. This induced rotor current in turn creates a magnetic field. The longer more correct explanation is that the stator's magnetic field induces an alternating current into the rotor squirrel cage conductors which constitutes a transformer secondary. The short explanation of the induction motor is that the rotating magnetic field produced by the stator drags the rotor around with it. The synchronous speed for 50 Hz power is: The “half speed” Picture 1 above has 4 poles per phase (3-phase). Where Ns is a synchronous speed in rpm, f is a frequency of applied power in Hz, and P is a total number of poles per phase (a multiple of 2). Picture 1: Doubling the stator poles halves the synchronous speed: Full speed & Half speed stator windings

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)